Dr. Estelle Glancy

The first female lens designer

Women have faced a glass ceiling in many fields, but the glass ceiling in glasses may have been the toughest to break through. During the first half of the twentieth century, only one woman managed to overcome the obstacles and rise to the top in the field of eyewear lens design, Dr. Estelle Glancy.

Glancy’s brilliance in mathematics and lab skills helped create the Tillyer lens, the most significant advance in vision correction of the 1920s. Millions of consumers benefited from the crisp, improved optics of this game-changing technology. They may not have known Glancy’s name, but they carried her innovative lenses with them at work, at play, or behind the wheel of an automobile.

But Glancy’s innovations extended beyond eyewear. She developed a breakthrough camera lens—a project requiring 200 pages of handwritten calculations—that helped photographers take sharper, clearer pictures. Experts in the field of television drew on her research in creating larger screens. Her work also contributed to advancements in telescopes, eye exam equipment and military optics.

In conjunction with International Women’s Day (March 8), the Optical Heritage Museum in Southbridge, Massachusetts is releasing images and documents in honor of Dr. Glancy. These materials come from the archives of American Optical, now part of Carl Zeiss Vision, where Glancy worked during her entire career.

FIRST LADY OF OPTICS

During her entire career, she was the only female scientist in the field of eyewear lens design. Now, forty years after her death, Glancy is starting to get recognition for her innovative work.

By Ted Gioia.

“She was a brilliant scientist and the first woman in her field,” remarks the museum’s executive director Dick Whitney, who has researched Glancy’s life and times. “Her story deserves to be told.”

Dr. Glancy earned her Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley in 1913. She was able to find work in Argentina for a few years, but eventually had to abandon her hopes for a career in astronomy. Seeing men without her training and credentials get jobs when she could not, Estelle despaired of ever using her scientific talents, and even considered taking a job in an airplane factory.

Dr. Estelle Glancy spent a decade on designs for the Tillyer Lens, the greatest breakthrough in consumer optics of the 1920’s

Dr. Anna Estelle Glancy, working with an early prototype lensometer

But in 1918, an opportunity came from American Optical, the largest supplier of eyewear in the US. There the eminent Dr. E. D. Tillyer believed Glancy’s skills could advance the company’s key research projects. Tillyer became famous in the field, but few know that the mathematical work that made his breakthrough lens possible was undertaken by his colleague Estelle Glancy. She later noted that this single project “took the greater part of ten years.”

More than three decades after joining the research team at American Optical in 1918, Glancy was still the only woman in her field. By then she was more than a pioneering woman in science, but also a catalyst for the innovations of others. Her papers were studied at universities, her patents advanced the field of optics, and her know-how laid the foundation for further improvements in vision correction for millions of people.

In eyewear, she anticipated many innovations long before they entered the marketplace. She filed a patent on progressive lenses in 1923—a half century before these became widely accepted as a superior alternative to bifocals and trifocals. She developed the first lensometer to measure the power of a spectacle lens, now a standard piece of equipment in optical dispensaries. Her work on tracking the comet Morehouse inspired the 2012 film 1908 c.

An article on Glancy from 1948 said that although American Optical employed five thousand people, probably only a half-dozen could understand the nature and depth of her research.

Today, very few people know about Estelle Glancy, even in the field of consumer optics. Whereas her college roommate Phoebe Waterman Haas, who gave up science when she got married a few months after earning her degree, had an observatory at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum named in her honor in 2013. Haas and Glancy received their doctorates on the same day, the first women at Berkeley to earn PhDs in astronomy, but only Glancy pursued a career as a scientist. Phoebe married the chemist Otto Haas and didn't pursue a career. She did, however, maintain an lifelong interest in astronomy and three years ago the foundation her son Thomas established gave the Smithsonian $13 million for a public observatory that was named for his mother. Looking at their respective contributions, it is hard to understand how Dr. Glancy remains virtually anonymous.

At the time of her death in 1975 at age 91, Glancy had been retired from American Optical for almost a quarter of a century. But by then evidence of her impact could be seen everywhere—from the progressive lenses that were finally accepted as the best vision solution for presbyopia to the televisions and other screens at homes and workplaces. “Forty years after her passing, she is starting to get some notice and respect, both for her scientific achievements and her pioneering role as the first lady of optics,” remarks ZEISS vice president Karen Roberts. “It’s about time”.

Dr. Estelle Glancy was the mastermind behind the progressive lens.

Dr. Glancy

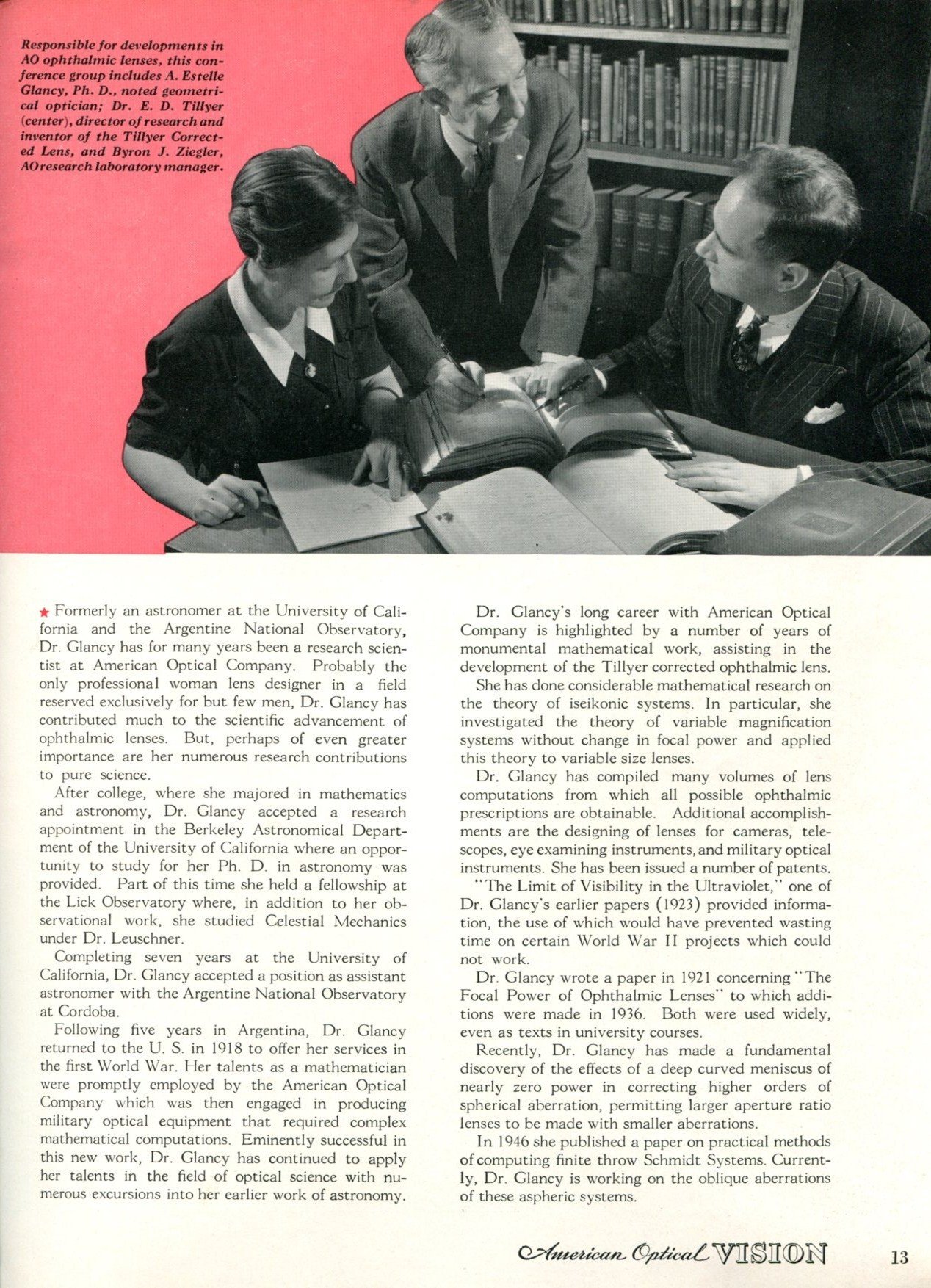

An extract from AO Vision - 1947

Children

Creating cool eyewear for kids

You might also like…