Todd-AO

Movies: Made by Vision Care

When optics disrupted Hollywood

In the 1950s, American Optical transformed cinema with its Todd-AO film technology

By Ted Gioia.

Hollywood needed something exciting in the 1950s to compete with the newfangled home entertainment gadgets, from television to hi-fi record players, keeping people out of movie theaters. In an unprecedented move, studios turned to a visioncare company for help—specifically to American Optical (now ZEISS). The result of this unusual partnership would change the course of cinema history.

Before turning to AO, Hollywood had already tried everything from 3D films to the elaborate Cinerama process, which required three synchronized 35 mm projectors and a special curved screen. But none of these proved scalable for widespread use. Mike Todd, famous today both as a movie producer and for his marriage to Elizabeth Taylor, was determined to find something better.

Todd soon learned that only three companies in the United States had the technical capabilities to solve his problem: Eastman Kodak, Bausch & Lomb or American Optical. After researching these options, Todd decided that AO was his best chance of success.

At a meeting with American Optical’s Dr. Brian O’Brien, Todd handed over a certified check for $60,000—that would be worth more than half million dollars in today’s terms—and said, “Let’s talk business.” For over a century, AO had stood out as the leading provider of eyeglasses and optical technologies in the United States, but suddenly it became involved in a completely different project. Would it be possible for an expert in lenses and vison to reinvent the movie business?

A team of 100 AO employees worked on this high-profile project and responded with breakthrough developments, including a 12.7 mm ‘bugeye’ lens that could photograph a stunning 128 degrees, almost as much as Cinerama offered with three cameras. Film stock was expanded to 250% of the size of standard 35mm and the on-screen results were described as “a sense of participation in the action on the screen” by the New York Times to its readers.

On June 22, 1954, Hollywood executives watched their first screening of the Todd-AO footage in a private showing on the MGM studio lot. Hollywood Reporter, the leading journal for the movie industry, gave its verdict: “The demonstration proved amazing full-screen clarity which was not diminished from positions up close at the sides of the screen… This has strictly big-time road-show possibilities.”

Audiences agreed. When the Todd-AO process made its commercial debut with the release of Oklahoma, the following year, moviegoers were dazzled by the bold, sharp images and vivid colors. Over the course of the next two decades, studios turned to the Todd-AO process for most of their blockbuster films, including The Sound of Music, Cleopatra, Around the World in 80 Days, The Alamo, South Pacific and Patton.

In a curious side note, Dr. O’Brien found that his work on this new movie technology distracted him from his ongoing research into fiber optics. O’Brien had already made a breakthrough discovery, learning that a low-refractive-index coating could improve light transmission in optical fibers. But now he was so busy helping out Hollywood he had little time for this project. Since that time, the market for fiber optics has grown to $5 billion annually, and it’s possible that American Optical lost out on a larger long-term opportunity by its detour into the entertainment industry.

Dr. Brian O’Brien of American Optical (center) poses with Richard Rodgers (left) and Oscar Hammerstein (right), composers of Oklahoma!, at the New York premiere (1955)

The TODD-AO innovative projection system created a 128 degree image on movie theater screens

“There are so many exciting chapters in the history of American Optical and 20th century eyecare,” comments Optical Heritage Museum Director Dick Whitney, “but this may have been the most glamorous of them all.”

Despite modern technology, the quality of the TODD-AO process can still be seen today. In a recent re-release of Oklahoma, fans were amazed at how well the old technology still delivered on its initial process. “There are no scratches and specks to be seen,” one reviewer marveled. “No grain is visible at any point in the 145-minute film. The picture has a nice, silky sheen that is like nothing you have ever seen before, which is shocking considering that this was filmed in 1955 and even the best restorations tend to leave a few tell-tale signs of age.”

It’s safe to suggest that movie lovers throughout the world can thank the R&D team at AO for their incredible effort and achievements in helping shape the film industry as we know it today.

Explore some of the other movies filmed using the TODD-AO process. You have probably seen them before...

Dr. Estelle Glancy

The pioneer of modern lens design

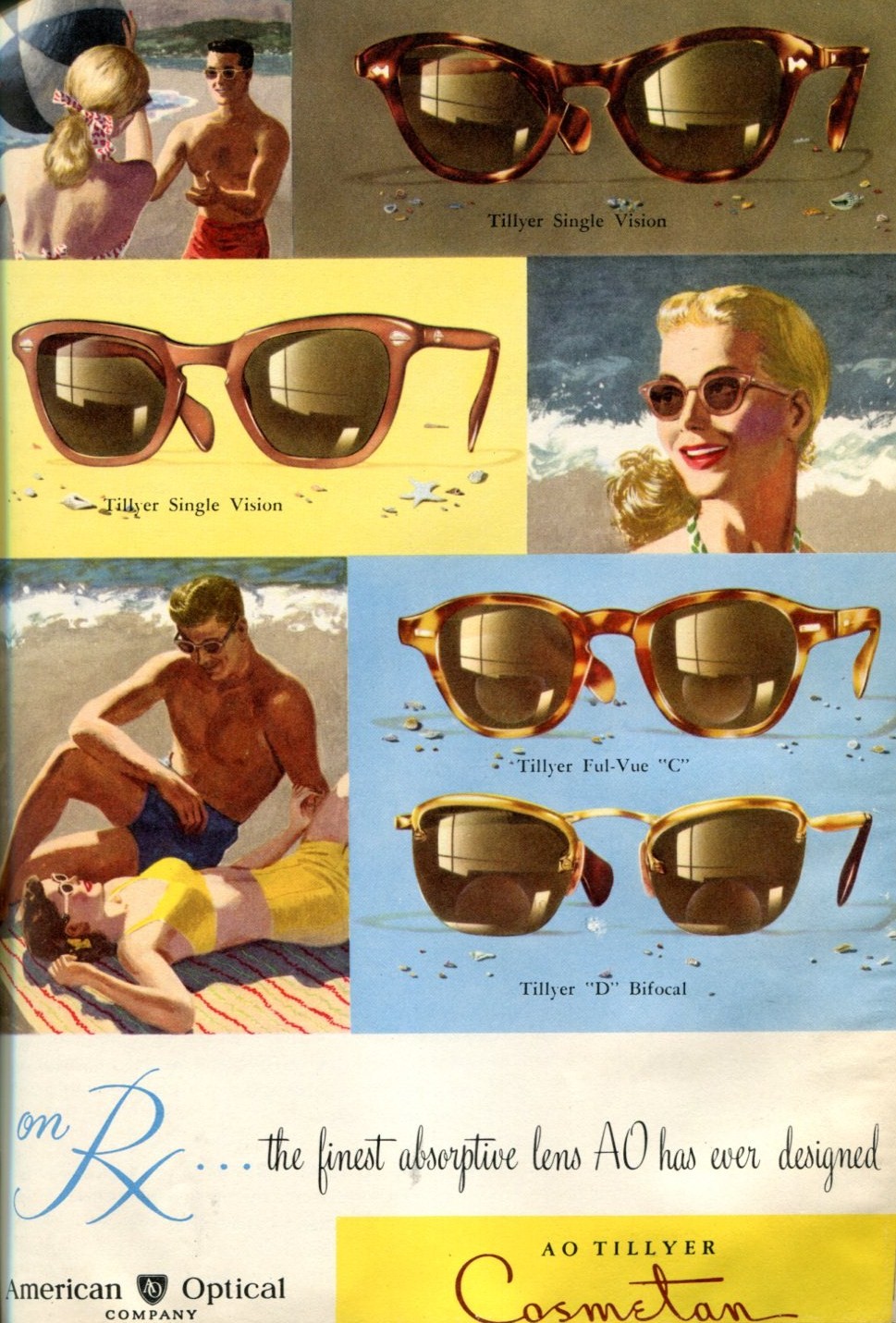

Sunwear

Keeping cool while the weather heats up

You might also like…